Podcast

La Rambla, that great thoroughfare in Barcelona, stretches from the city centre to the sea. It is the street where every new visitor wishes to be – and sooner or later they all make it. To walk along it, at almost any time of the year, is to be swept up in a surging human tide that never stops. It may judder to a halt under its own weight but it rolls on again. In the harbour, cruise liners wait like landing craft, loaded with fresh invaders. Not for nothing did a recent acerbic graffito on a wall in Barcelona demand: ‘If this is open season for tourists, why can’t we shoot them?’

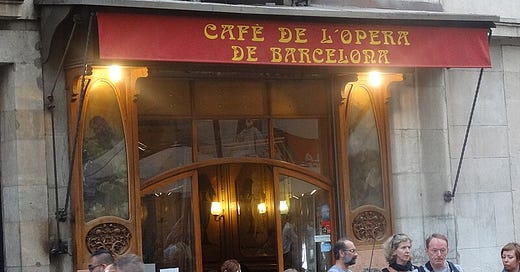

Where then on la Rambla might it be fun to recuperate or to escape the flood? The answer is a decent café and the Café de l’Opera is one of those rare refuges.

Photo: Jordiferrer

The entrance is modest, discreet, and easy to miss. Happily, a useful landmark looms nearby. The oldest opera house in Barcelona, the Gran Teatre del Liceu, is right across the road and seems almost to keep a fond eye on its smaller namesake over the way.

The Liceu theatre dates from the mid-eighteen hundreds but the Café de l’Opera is rather older. It began in the 1700’s, as a boarding house and a tavern, then served as a staging post for carriages setting off to Madrid. It has been in its time, a restaurant and a chocolatier. In the 19th century, when Viennese coffee house frills and fancies were all the rage, the café acquired its wooden walls, persistent mirrors and glitzy chandeliers. In the early 20th century, the passion for art nouveau was left, painted on the café walls, flowers, flounces and girlish attic dancers. The horseshoe bar is handsome and the upstairs room is a peaceful space. Customers may choose to stand out, or fade into the background, useful options a good café offers its friends.

All through the Spanish Civil War, Café de l’Opera never closed. It survived Franco’s assaults and kept going. It was a favourite of Barcelonans, a welcoming water hole for coffee, conspiracy and consolation. It was also a favourite hangout of the foreign volunteers who served, reported and perished in the International Brigades. But walk in today and you see and feel something no longer fits. The Café de l’Opera has escaped unchanged but all around it has changed utterly.

Outside on la Rambla, blindfolded by the phones pressed to their eyes, the tidal bore of tourists surges past the café doors. Café de l’Opera is a world away from la Rambla’s most successful and popular specialities: tat and tapas, scooters and mime artists, pizza joints and pickpockets. In part, the problem is about money. When the city of Barcelona decided no longer to control rents, the profit margins, so tightly allied to the life expectancy of any café, took a major hit. No doubt the developers are circling the last historic locales on la Rambla like hungry sharks. After all, in the wrong hands, it would be easy to convert Café de l’Opera into half a dozen tapas bars.

But it’s about more than money. Cafés, like those who love them, age and decline - and holding things together is never easy. Café de l‘Opera was once, in its welcoming, convivial way, one of the most sophisticated and congenial sets of rooms in Barcelona. That is true no longer. A sense of regret permeates its dim interior. It has outlasted its time and its purpose. Worse still, it can’t quite remember what its time or its purpose once were. It survives on sufferance, on borrowed time and it shows. The service is not so much sedate as sedated when not a touch irascible. Even the coffee is not what it might be. And that in Catalonia - where it is very hard to find a bad cup of coffee.

The Liceu opera house over the road has always supplied a good many of the café’s patrons. But that number is declining. I was almost alone when I sat down in the rear of the café, far from the rush and roar of the crowded avenue. The comfortable wooden bar was home to three black-clad film crew, taking a break from a film shoot in the Liceu Theatre. A bunch of musicians breezed in, fresh from an opera rehearsal, and settled down for a few beers, their dark cello cases standing like shadows at their backs. Here and there, a sprinkling of bemused tourists faced their own faces in the many mirrors, wondering, perhaps, what on earth the painted floral fantasies on the walls were all about. Did those dancing girls, garlands and elaborate woven baskets perhaps hint at something so incorrect it might be unwise to post your pictures online?

Christopher Hope